The diary of Antonia Macnaghten née Booth[1]

Antonia Booth was my great grandmother. She died in 1952, 5 years before I was born.

Diary entries are in black,

commentary is in blue

and footnotes are below in black.

Entries are captured in months.

This blog begins with the year 1898 even though the diaries start in 1894 because it is more straightforward to introduce the main characters in this year. I shall return to 1894 in a while.

If you think I’ve left something out please do let me know or if there is a factual error please tell me gently.

March 1898 continued

Went with George to see …. found Eleanor Clough[2] there and Margaret Phillimore. We walked across with Eleanor and on to Arthur and Sylvia’s where we found the whole family.

Arthur Llewelyn Davies was a cousin of Antonia’s on the Booth side. He was a barrister. His sister was suffragist Margaret Llewelyn Davies who was 30 years General Secretary of the Women’s Cooperative Guild and an extremely significant campaigner across a range of areas – fighting to gain a political voice for working-class women in particular.[3] His brothers, Theodore and Crompton were also very close friends of the Booths. Theodore spent a great deal of time with the Booths at Gracedieu and was reportedly in love with Antonia’s sister Margaret at one time. Arthur’s niece was Theodora Llewelyn Davies, the first woman admitted to the British legal profession’s Inner Temple in 1920 who was part of Malcolm Macnaghten’s chambers.

Arthur met Sylvia du Maurier, a great beauty of her day as you can see (and daughter of cartoonist George du Maurier, sister of future actor Gerald du Maurier and aunt of author Daphne Du Maurier) at a dinner party in 1889. They became engaged shortly thereafter. He married her in 1892, and they had five children, all boys, who were the inspiration for Peter Pan by J. M Barrie. Barrie was a close friend of the Llewelyn Davies family whom he met in Kensington Gardens and when Arthur and Sylvia died he became the boys guardian though it is not clear that this was what Sylvia intended when she wrote her will.

Kensington Gardens was a favourite and a convenient place for Antonia and her friends and their nannies and maids to take children.

Some of the material below comes from a marvellous website that features a database curated for over 40 years by Andrew Birkin.[3]

When Sylvia du Maurier accepted Arthur Llewelyn Davies she knew that he was not enormously wealthy as she told her close friend Florrie:

[no address]

Letter from Sylvia du Maurier to her close friend Florrie Gay, 26 March 1890

Wednesday

March 26th [1890]

My dearest girl,

What will be your feelings when I tell you that I am engaged to Arthur Llewelyn Davies! Will you write and say sweet things to me? – at the present moment I don’t know what I feel like but I know I should like to see you and talk to you. The only thing is I don’t know if I shall have time. I go to Westmorland on Monday I think to stay with Arthur’s people – don’t look forward to [???], we shall have 2nd and no more – you must have the £s. But still it is better to have 2nd with someone you love than a lot with someone else, isn’t it Florrie?

It will be a long engagement I think but don’t say anything about this to anyone because I barely know myself yet, but I always like you to know as much as I know.

Write soon

Yours always

Sylvia

You have seen him haven’t you at Trixie’s?

‘There seems to be a jump in thoughts, from nerves at the approaching visit, to something about “you must have the £s” – money she’d promised her friend Florrie? And then this idea that she’d sooner settle for a 2nd class life-style on Arthur’s meagre salary “than a lot with someone else, isn’t it Florrie?”… it was to Florrie Gay that Sylvia wrote her heartbreaking letter after Arthur’s death, and to whom she turned in her Will, “to make a home for them till they are out in the world.”…’[4]

Sylvia was fond of both Antonia and her husband to be Malcolm Macnaghten. This is Sylvia’s letter to Malcolm Macnaghten on his engagement to Antonia Booth:

Tuesday 31 Kensington Park Gardens

My dear Malcolm Really it is the very nicest thing that ever happened if I may say so my heart his full of affection for her and for you. After all my little indiscretion has come true and although I was very distressed when I was told, though kindly of it (my indiscretion) now somehow I am not sorry anymore. I cannot write all I feel but … I had seen both this afternoon and then perhaps I could have said a little of it. I wrote a short letter to dear Dodo but I posted it this afternoon to Gracedieu before Arthur got back. All the little boys send warm congratulations

I am delighted

Yours affectionately Sylvia Llewelyn Davies

Antonia’s future husband Malcolm Macnaghten helped Arthur to find employment as a barrister a year before Arthur died:

12 Nov. 1906

My dear Arthur,It was very good of you to write, for we were anxious – and it was indeed a very great relief to get your letter.

The weather must be very much against you at present – but I trust that if you give up coming to the Temple for the present, the trouble will soon abate.

Father is very ready to speak to the L{ord] C[hamberlain] and was going to do so – but of course the latter’s illness makes it impossible for the present. I understand from Father that at a meeting of the Council of Legal Education he said something about you and about his intention of speaking to the L.C. and everyone present– I don’t know who they were – joined in commending you, and Father was, I gather, authorised by them to back up what he may say with their support and concurrence. So I do not think there need be any doubt but that if, when the L.C. is well again, you are wanting a post in his gift, your claims will be so strongly supported as to make it reasonably certain that you will get what you want.Goodbye, and many thanks for your letter and don’t answer this.

Yours aff. M.M.M.

Sylvia’s friendship with Barrie did not escape comment in their social circle. Here is Gerrie Llewelyn Davies (the wife of John sometimes called Jack Llewelyn Davies) talking about Sylvie ‘going off’ on holiday with Barrie and the boys in 1905. Gerrie was notoriously bitter about her mother in law:

Gerrie Llywelyn Davies speaks with the Edwardian accent of her generation and her class. She speaks as if she assumes all this is common knowledge and her tone brooks no opposition. It reminds me why it was hard to get these Edwardians to tell one what one wanted to know!

Her is another example, Virginia Woolf:

Arthur died in 1907 and Sylvia in 1910. After Sylvia’s death Antonia wrote in her diary:

August 1910

We heard today that Sylvia died on Friday I think she must have had all the boys with her. Oh what a tragedy it was the night of the storm here. Now she’s quite gone, unthinkable. We had to get ready our party for Neil’s grandchildren but we thought and thought of her and Arthur and all the old days and how wonderful and complete they were with their boys. Certainly, we shall never know anybody like them both. We tried to write to Crompton in the evening.

There is more to say about the Llewelyn Davies’ but I will leave it there for now.

George and Tom and I went to dinner with Alice and Jack, Hester and Billy Ritchie[5] were there. Met Urith and Tom Coltman, Jamie and Olivia, Hester and Billy, Theodore, Dighton Pollock and Mr Bill. Went to Southwark.

Meg came back from Newnham. I went to dinner with the Cloughs[6]. Dighton took me into dinner we went on afterwards to party at the Lushingtons[7] consisting entirely of very familiar Massing- and other-birds[8].

‘In spite of Mary Booth’s (Antonia and Meg’s mother) antipathy to organised education for women, she suggested that her second daughter should try for a place at Newnham[9]. Easier said than done as Meg had no Latin. After six months’ hard work however she passed her Little-go, went to Cambridge in the autumn of 1897, and found there the right setting for her pilgrim gaiety.’[10]

Flora Russell and Sue Lushington came to lunch and we went to the Cat and the Cherub[11] and were thrilled to sticking point.

watercolour, circa 1890?

NPG 4385

Flora Russell was the daughter of Lord Arthur Russell and Lady Laura de Peyronnet. She was a watercolour painter and her portrait of Gertrude Bell (1868-1926), traveller, spy and archaeologist, is at the National Portrait Gallery. Bell was a childhood friend. In 1965 Gimson and Eustace recorded Flora Russell, at the time 96 years old, whose speech they regard as a “good example of a certain kind of Victorian English”.

The Russells at the time of Flora’s youth were part of the same London intellectual elite as Antonia. ‘They lived at 2 Audley Square, Mayfair, and their house was frequented by Leslie Stephen and his daughters, Virginia and Vanessa; Mrs Humphry Ward; Henry James, John Singer Sargent and Vera Brittain. She was briefly engaged to George Stephen, older stepbrother of Virginia Woolf. Hearing the news, Woolf sent a congratulations telegram: “She is an angel” and signed with her family nickname “Goat”. The telegram delivered was “She is an aged Goat”. George Stephen later commented that he thought Woolf was referring to Flora Russell’s reluctance to ally herself with the Stephen family. Woolf denied this and said the mistake was due to her handwriting.’

This is the play that thrilled Antonia, Flora and Sue ‘to sticking point’:

THE CAT AND THE CHERUB.

” There is no temptation to dwell afresh upon the features of the well-known piece of Mr. Charles Parley Fernald. The picture it supplies of life in the Chinese quarters of San Francisco has, in spite of the necessarily conventional nature of the dialogue employed, convincing truth and realism, and the spectacle the revenge executed by the learned Doctor Wing Shoe upon the assassin of his son, remains inexpressibly weird and gruesome. ..Mr. Sidney Drew, the much-perplexed hero, shows his old comic lightness of touch. His performance is once more received with constant laughter and applause, excellent support, being still afforded Misses Doris Templeton, Victor, Clarke, and Messrs. Charles Rock and Frank Atherley. Mr. De Lange’s picture of the dancing-master remains thoroughly comic, and the schoolroom revels have undiminished vivacity.

Globe – Thursday 02 June 1898

The actors in this play were English. The representation of the Chinese and Chinese culture in English plays of the time was interesting. There were pantomimes of course, based on the Aladdin story, plays enacting the arranged-marriage tragedy supposedly depicted on willow-pattern plates, melodramas where a Chinese woman falls in love with a Briton, and believe it or not “pyro-spectacular” productions depicting contemporary military conflicts in China. The Chinese Mother (1857), by “Dr. Tanner,” was anomalous, a sympathetic treatment of Chinese women who kill their infants not out of barbaric cruelty but because of famine.[12] Recent academic commentary on how the British conceived of China in Victorian times has argued that Western views of the East were based on a constructed reality that envisioned the Orient as ‘a monolithic “other,” diametrically opposed to the West’.[13] Other commentators have focused on the vast amount of Chinese material culture the British consumed in the eighteenth and nineteenth century. They view these Chinese imports as a catalyst for the hostile shift in British attitudes towards China in the early 19th century in that they “provided a material and visual context through which the vast, even overwhelming power and history of the Chinese empire could be re-imagined as fragile, superficial, and faintly absurd.”[14]

It must certainly be acknowledged that there was a time when anything Chinese was avidly collected in both Europe and America. Grand mansions would have a ‘Chinese Room’ stacked high with gleaming, colourful porcelain in display cabinets and a Chinese inspired garden. It was common amongst the upper classes to own Chinese ornaments, silks, lacquer-work, furniture, willow pattern plates, sedan chairs, wallpaper, gardens with pagodas … everything. From the mid-17th century through to the early 19th century this great fashion for the ‘Oriental style’ flourished and, of course, it was given the name ‘Chinoiserie’ in France where the fashion reached its height of popularity. It influenced many different kinds of interiors including those of London artists of the period.

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s Library in Townshend House, St Johns Wood, London, 1884 by Anna Alma-Tadema. The ground and the wall were covered with tatami mats. The textile hung against the wall looks like batik fabrics from Southeast Asia. A cattail leaf fan reflects a strong Oriental style.

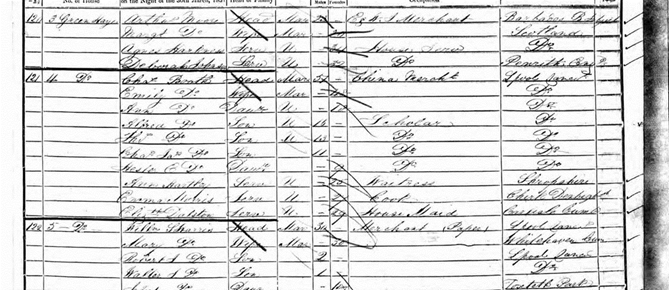

So how was Antonia connected to China and Chinese culture? In the 1851 census her grandfather’s profession is listed as ‘China Merchant’ which is surprising because several accounts of his life suggest he was only a corn merchant.

That he changed the focus of his business from corn is not hard to understand as in the 1850s the complexity of the corn market is well known. Merchant ships filled with Chinese porcelain, furniture, textiles and other Chinese goods continued to sail into Liverpool port and must have seemed a more dependable business.

Liverpool saw the first Chinese merchant sailors in 1850s, when Alfred Holt & Co., established its shipping line from Shanghai to Liverpool and recruited Chinese sailors, making the China Town in Liverpool Europe’s oldest.[15] Antonia’s aunt Anna was married to Philip Holt (who came from another non conformist family in Liverpool) who founded the Holt shipping line and was also part of a family shipping empire. When he was young Antonia’s father was apprenticed at Lamport and Holt, another shipping company that the Holts part owned. The Booth companies had agents in China who supplied skins for their tanneries and her cousin Paul Crompton worked for the Booths in China, then ran their American concerns and later tragically died with his family on the Lusitania.[16]

Antonia will have been familiar with all kinds of chinoiserie in her life in the form of domestic interiors and artefacts.

Antonia lived in a London house packed full of oriental and ‘other’ things. Here are her mother Mary Booth and her sister Margaret Booth at 24 Great Cumberland Place in 1897. In 1876, when Mary Booth was redecorating Grenville Place, Mr Macaulay, Mary Booth’s father, teased his daughter about her ‘Alhambra Palace’ and you can see that the panels in the doorways the Booths have installed are Moorish.

Antonia enjoyed China tea like so many other English ladies. She collected Chinese and faux Chinese ceramics. She collected at least two Chinese costumes probably for use at fancy dress parties. Her daughter Mary wears one at a party on board a Cunard ship bound for New York in 1926.

One of Antonia’s Chinese robes. It is an early nineteenth century silk robe of high status.

Costumed parties were very fashionable at the time for children and adults.

There seemed to have been a competitive element to some of these events.

The Ladies’ Fancy Dress Ball at Cheltenham… There were any number of pretty dresses, one of the best was a poppy, harmony in scarlet, with the green stems apparently growing up the skirt, the waistband of the same shade of green… A Spanish duenna, with her high comb and black satin mantilla bordered with lace falling over a black skirt and red Senorita jacket, was singularly becoming to the dark beauty who wore it. …A Summer Shower in silver-glistening chiffon, with white roses, was a pretty conception. But the honours were not all with the ladies. A stalwart Mandarin in a real Chinese costume, and Dr. Nikola, with a black cat on his shoulder, attracted much notice.

St James’s Gazette – Wednesday 26 January 1898

Antonia will also have been aware of the Chinese in London at the time. Her father Charles Booth mentions the presence of the Chinese in East London in his notes that contributed to his study of poverty in London.

‘In Shadwell High Street or Ratcliff Highway we “may chance to find John Chinaman leaning against the shop door or ministering to the wants of his Asiatic customers. If we step inside, and take care not to alarm him, we may find twenty or thirty Celestials or Malays are dreaming over their pipes.’[17]

Charles Booth used for some of his observations the notes of an Inspector Carter of the Limehouse District who accompanied George Duckworth on his walks in the East End.

‘Chinese cooks sometimes escape from aboard ship and hide in Limehouse Causeway. But with the help of the chap at the Chinese general shop Carter generally can put his hand on them. That means a sovereign into his pocket. (The Jap) is a good sailor and more and more are being employed on English ships…. When he comes to London he drinks beer, gets drunk and runs after women.’

Inspector Carter

Both Booth and Carter characterise at least a corner of Limehouse as a kind of early Chinatown in the East End.

[1] Antonia Macnaghten née Booth was born on 3 February 1873. She was the daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Booth and Mary Catherine Macaulay.1 She marred Rt. hon. Sir Malcolm Martin Macnaghten. She had four children. She died on 18 January 1952 at the age of 78 leaving 53 diaries which are transcribed here.

[2] Eleanor, née Freshfield, wife of Arthur H. Clough (1859–1943), son of the poet; she was the daughter of Douglas and Augusta Freshfield.

[3] The main content of the database is research material he gathered in the course of writing his 1978 BBC television series The Lost Boys, as well as his later biography, J M Barrie and the Lost Boys (Yale University Press), while subsequent items were acquired through donation or purchase from numerous sources.

[4] https://jmbarrie.co.uk/letters/sylvia-llewelyn-davies-to-florrie-gay-1890 From the Andrew Birkin database website.

[5] Billy Ritchie was to marry Antonia’s sister Margaret.

[6] They were closely related to the first principal of Newnham, Anne Clough.

[7] Vernon Lushington was the fourth of Stephen lushington’s sons. Vernon became a distinguished lawyer and Secretary to the Admiralty. From the late 1850s Vernon and his brother Godfrey became increasingly involved with Beesly, Harrison, Crompton, J N Bridges and Congreve in helping the Labour Movement. Sidney and Beatrice Webb wrote of ‘the talented young barristers and literary men, who, from this time forward became the trusted legal experts and political advisors of the leaders of the Trade Union Movement’ Lushington was a close friend of the social reformer Charles Booth and their two families were often together. https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/search/archives/7f76efbc-f3a9-3063-a1aa-fe5a4a4546f6?component=9e62cade-2bf4-3262-9472-f0c068657645

[8] Margaret Lushington, the daughter of Vernon Lushington was born in 1869. In 1895 she married Stephen Massingberd of Gunby Hall, Lincolnshire. She died in 1906.

[9] Newnham began as a house for five students in Regent Street in Cambridge in 1871. Lectures for Ladies had been started in Cambridge in 1870. These built on the reputation of the University; but Cambridge itself was a small market town with a thinly-populated hinterland and for many who wanted to attend, it was too far away to travel in and out on a daily basis. Urged on by Millicent Garrett Fawcett, later to become a celebrated campaigner for women’s suffrage, the philosopher Henry Sidgwick, another of the organizers of the lectures, risked his own credit in renting a house in which young women attending the lectures could reside. He persuaded Anne Jemima Clough, who had previously run her own school in the Lake District, to take charge of this house.Demand continued to increase and after moving houses twice, the supporters of the enterprise formed a limited company to raise funds, lease land and put a purpose-built building on it. Newnham Hall opened its doors in 1875. In an address to a meeting of sympathizers and potential donors in Yorkshire that same year, Anne Jemima Clough explained the rationale for the institution:

“How much more effectually, & with how much less mental strain, a woman can study, where all the arrangements of the house are made to suit the hours of study, – where she can have undisturbed possession of one room, – and where she can have access to any books that she may need. How very rarely, – if ever, – these advantages can be secured in any home we all know, and it is surely worth some sacrifice on the part of parents to obtain them for their daughters at the age when they are best fitted to profit by them to the utmost.” https://www.newn.cam.ac.uk/about/history/history-of-newnham/

[10] Belinda Norman Butler Victorian Aspirations.

[11] By Richard Gathony https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Ganthony

[12] [Review of] Ross G. Forman’s China and the Victorian Imagination: Empires Entwined

[13] Said’s 1978 book on Orientalism

[14] Porter expands upon his treatment of Chinese goods in eighteenth century Britain in his 2010 book, The Chinese Taste in Imperial England.

[15] https://www.liverpoolchinatown.co.uk/history.php

[16] https://www.mikeredwood.com/booth-co/ https://purehost.bath.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/187955525/UnivBath_PhD_2013_M_Redwood.pdf

[17] https://hindzeit.wordpress.com/2016/01/30/charles-booths-london-1-the-myth-of-chinatown/comment-page-1/